Our Farm

History

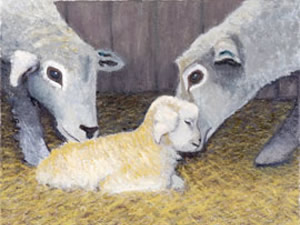

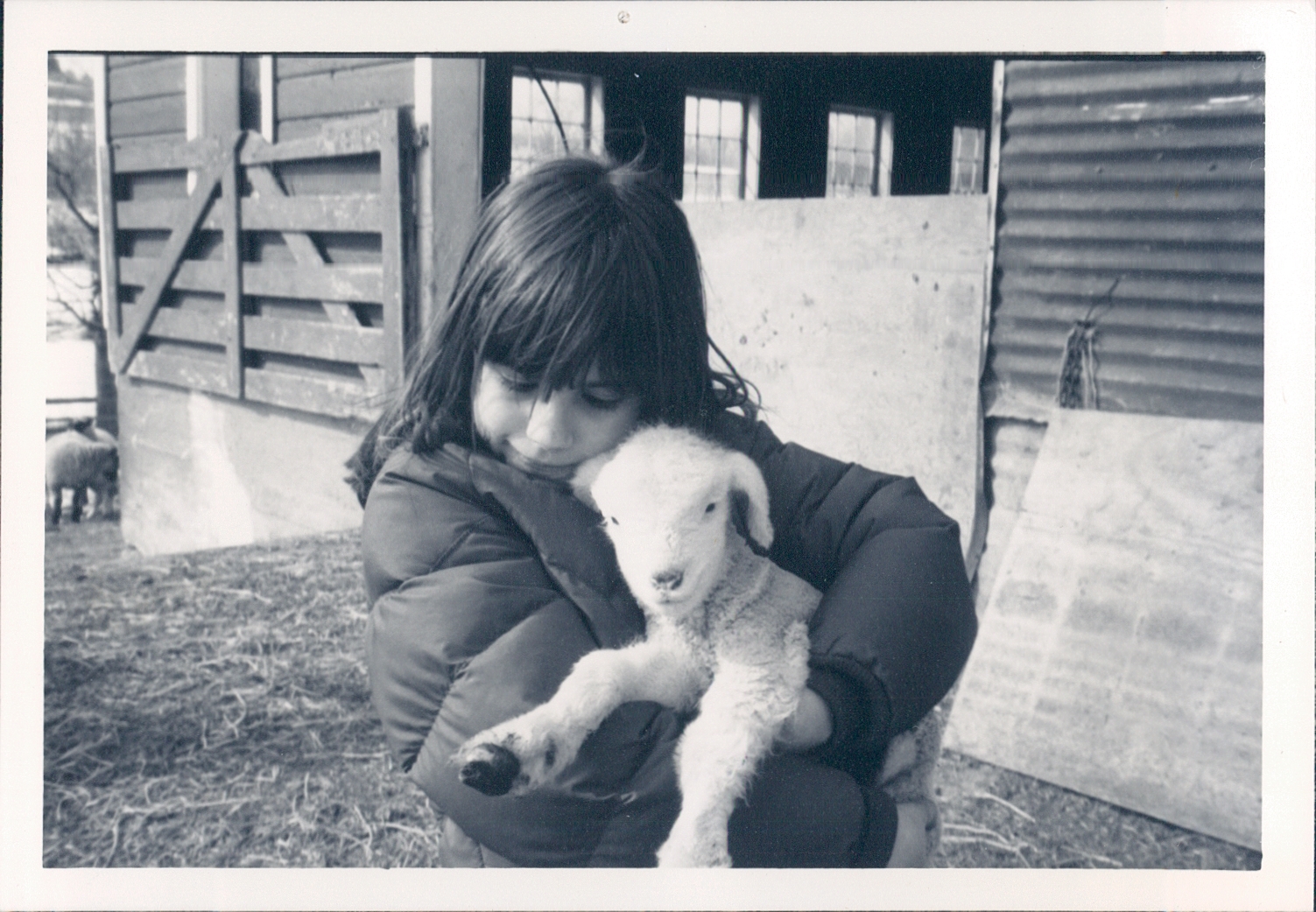

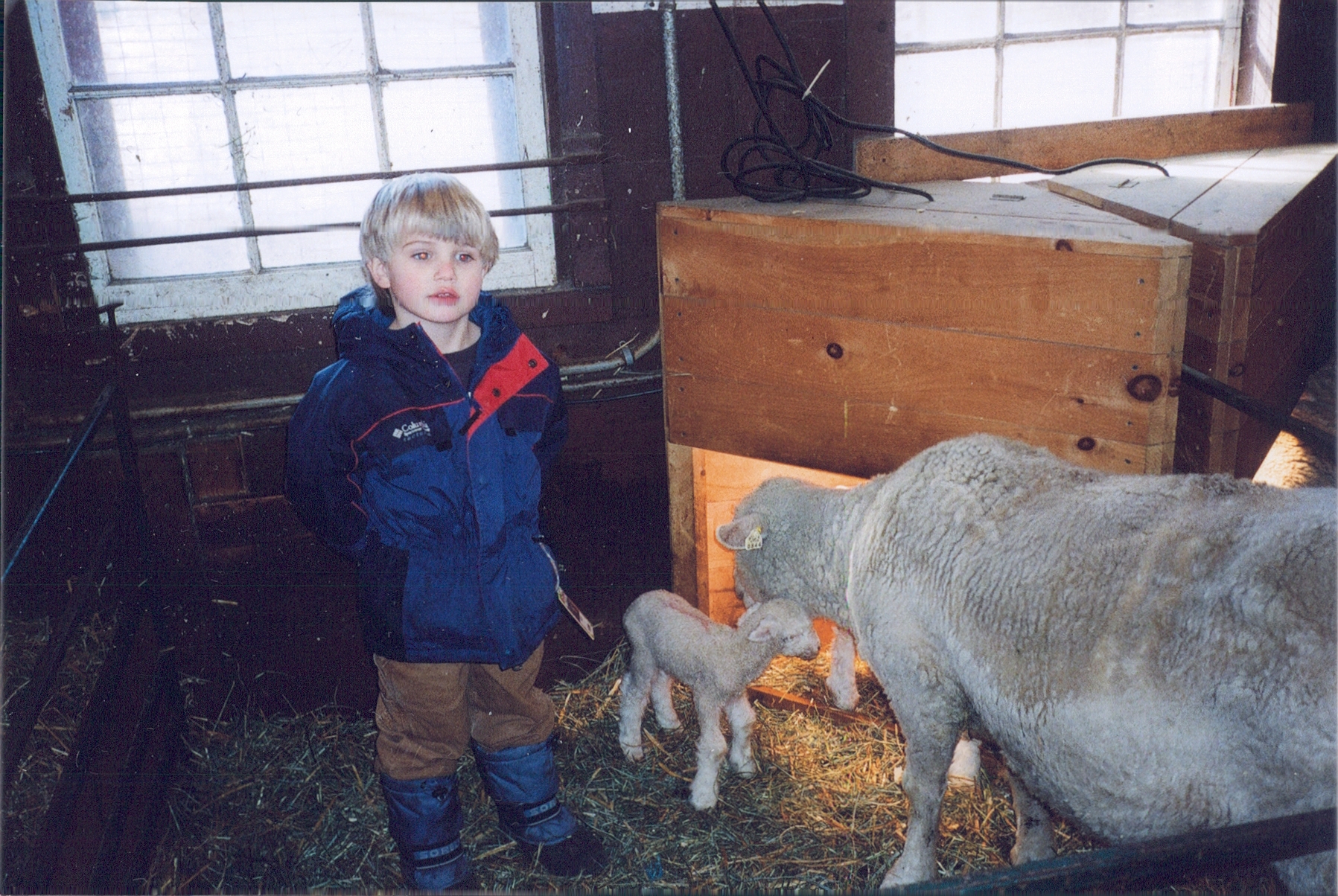

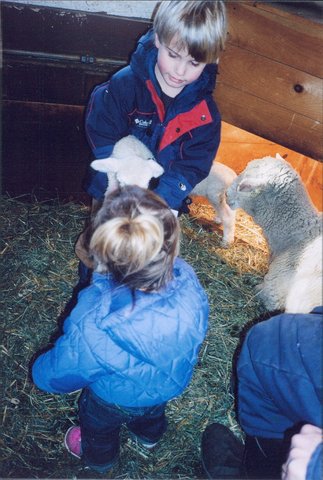

Elizabeth and Stephen Shafer got our first sheep in 1980 with the support and encouragement of her father and sister, who farmed in eastern Dutchess County NY. Our first ewes, not purebred, had been the subjects of the shearing demo at that year’s NYS Sheep and Wool Festival. At Wethersfield, the farm in Amenia NY founded in the 1930s by Elizabeth’s father, we began a very small Romney flock the next year. The first three ewes came from Brenda Bothe (NJ) ; the first ram, from Peter and Patty Drape (NY). With the very material assistance of our friends the Blundells and of the Wethersfield Farm staff we built up the Wethersfield Romney flock along with a fair-sized commercial-sheep operation.

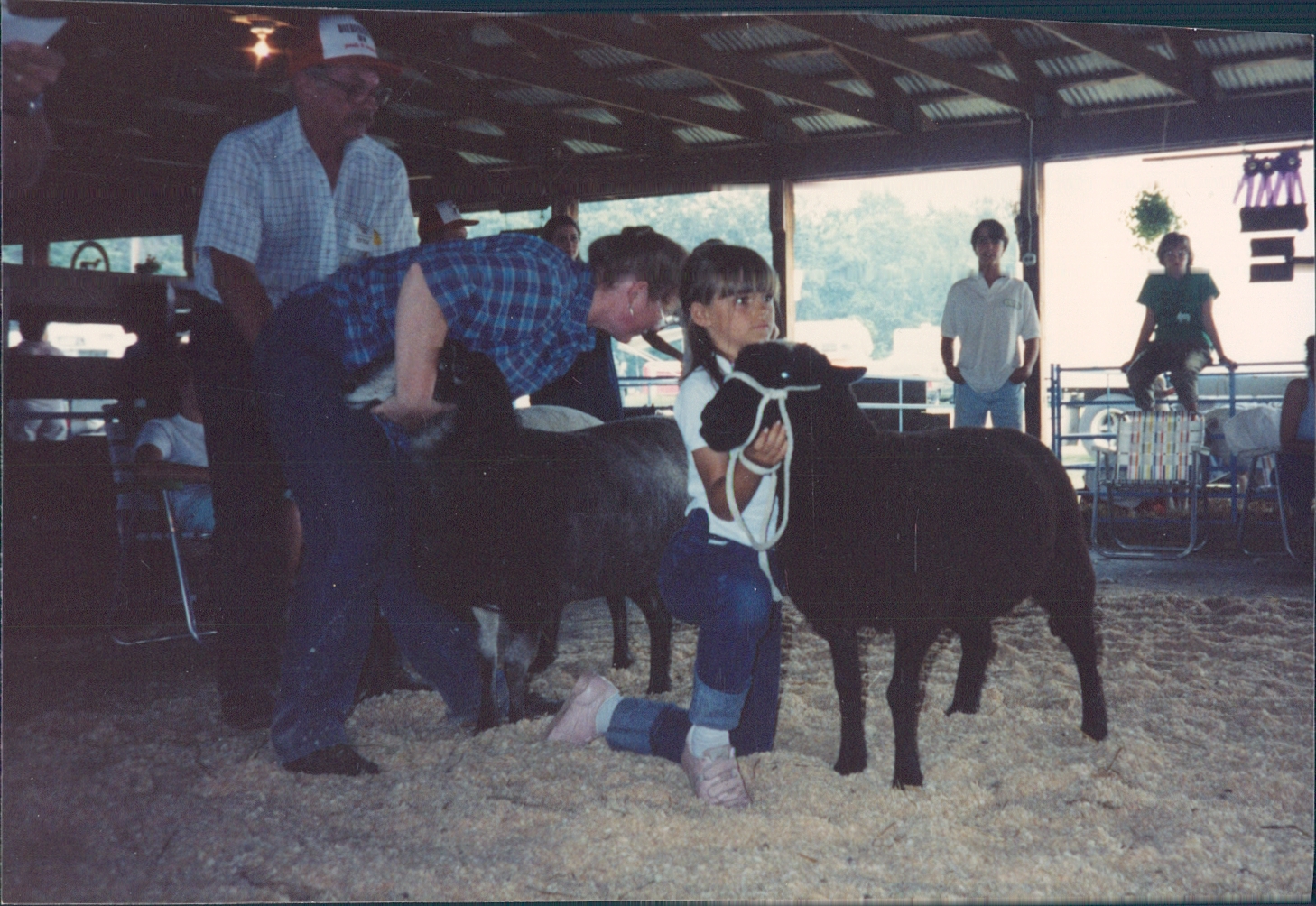

Wethersfield Romneys got Premier Exhibitor at the Big E in 1987 and 1988; Premier Breeder in 1988. At NAILE in 1988 Wethersfield had Grand Ch. Romney Ewe (If I remember right, she was a Bellairs.) Thus for 30 years this flock stood well at major eastern shows; see the Shows and Sales pages for details. Since 2017 we have just about stopped showing, to put more effort into “carbon farming ” for soil health.

In 1992 we moved from eastern Dutchess County to a farm in Saugerties, NY begun active in 1763. We changed the flock name to Anchorage, which had been the name of our new home since the 1890s. The move and the re-establishment could not have been done without the expertise of Randy Reuter, manager 1989-2000. Ian Stewart lent a strong hand 2002-2003. In 2004 we were privileged to have Graeme Stewart come as manager. Not only was Graeme indispensable to Anchorage, but he also had many roles in the Dutchess County Sheep and and Wool Growers Association (of which –no surprise–Lizbeth’s brother in law Roy had been one of the original organizers). Some years ago, Graeme was named Shepherd of the Year by the Association . He has judged sheep shows in MA, MD, NJ, NY, PA, VT and OH.

Our farm was cleared before 1763 by settlers of Dutch descent. In the 19th C. it was known as “The Brink Place” for Capt. John Brink, who fought at Yorktown and whose son Andrew piloted the North River Steamboat (later called Clermont) on its maiden voyage to Albany in 1809. On moving in we found a lot of old horse-drawn farm equipment from the early 20th C. and before. The barns had no electricity and no water except a seasonal spring. The slideshow takes viewers through four seasons at today’s Anchorage Farm.

Stephen wrote in 1996 “Anchorage Farm is a riverbluff woodpasture steading, with a glade, a force, a dell, a kill, an edge, a chine, a swale, a rill, a scarp, a hanger, holt, a steep, an oldfield, and a sheepwalk full of sheep.”

In 2014 we had to put down 19-year old Zephyr, the gray cat who is seen in some of the slide pictures. In 2015 Lava the guardian black llama had to be put down at age 14. He, too, appears in some of the slides. Daniel the tricolor cavalier spaniel who’s in one of the slides, died a few years ago. and in 2018 so did Jali at age 13, leaving Felix , who died in 2021. None of these dogs did a lick of work on the farm, of course, but they graced our home. In May 2023 we had the pleasure of welcoming “Summer,” a little lady who is the seventh in our series of tricolor Cavaliers.

In 2017 we described management this way, with an overture to “carbon farming:” Skip 2017 if you’ve read it before, go to 2018 below then to 2019

We run about 13 acres of perennial pasture, mostly rolling with one steeper hillsides. We use semi-intensive rotational grazing for the ewe flock until breeding season, when subgroups stay with one ram in larger paddocks longer. We fertilize the more level swards with long-stockpiled barn bedding waste. We don’t employ chemical herbicides for reasons like the one to your right: this monarch had just emerged when photographed on Sept 30 2018.

We do use chemical wormers regularly as appropriate to age and breeding cycle. Mature ewes are vaccinated against Vibrio. Lambs get lasalocid in their feed to one year of age for control of “coccidiosis.” Other antimicrobials by mouth or injection are given as needed for treatment of symptoms or prophylaxis against threats like neonatal pneumonia or chlamydia-caused abortion. A few years ago we used 4-3-3 by Amsoil as a foliar spray mixed with liquid lime on the two main pastures for two years, but have not applied anything except barn compost in the last five years. The liquid lime kept getting stuck in the sprayer nozzles.

In spring 2017 Stephen and Lizbeth were introduced to “carbon farming” by name when we joined the estimable environmental organization Citizens’ Climate Lobby. Certain CCL members, notably Jan Storm of Chatham NY, had perceived earlier that storing carbon in soil and trees through “regenerative agriculture” could improve soil health while removing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air. This low-tech method of sequestering carbon can make agriculture literally part of the solution to global warming instead of its being a part of the problem.

Note that crop and livestock agriculture accounts for only about 10% of US greenhouse gases/year, being a minor player in that sense. That proportion seems outsized to many environmentalists, especially vegetarians, as agriculture provides only 1-2% of GNP In that sense the sector’s share of GHG is unduly high. Without agriculture, however, we would all starve, and without animal agriculture properly done the world’s soils would go to ruin. The ag carbon footprint can be made lower by regenerative farming without long-term detriment to farmers and ranchers and without reducing the availability of nutritious food. Quite a few farmers and ranchers who have gone regenerative report that after a couple of years their profits are up and their lives are happier. Here’s a success story from Kansas, another from Cumbria in England and another from New Zealand . For more; just ask sqs1(at)columbia.edu for the “success stories” list of over 100 outfits.

In concert with Graeme, we have launched several related projects on carbon management here. Some are described more in blogs from our web site:

- Assessing our farm’s current carbon footprint (C-print) using our own tabulations as well as USDA COMET-farm; the English counterpart Farm Carbon Calculator; and the Scottish Coolfarm Tool.

- Lowering the C-print immediately We now buy electricity for the barns and the manager’s house from Green Mountain Energy (100% wind) through Central Hudson. We had installed solar photovoltaic panels on one barn roof several years ago, but they don’t have the capacity to supply everything.

- In 2019 we installed air source heat pumps in our house and in 2022 put a geothermal system into the manager’s house.

- Assessing the health of the soil under our pastures by sampling for soil organic matter (SOM) and forage testing

- Assessing how we compost barn bedding waste and spread the results

- Assessing utility of manure and urine dropped on the ground

- Estimating carbon storage in trees, which cover more than half our total acreage.

In Aug 2018 and Jan 2020 we have rewritten, added to and commented on what’s above based on observations in the past two years.

The 61 acre place has about 30 acres of woodlands. Most of the 6500 or so trees are less than sixty years old, though there are some grand oaks older than that. About 27 more acres are now, or were as recently as 50 years ago, in pasture. Maybe 4 acres are barnyard plus building footprints plus farm roads plus stream area. Some erstwhile grazing ground is now practically inaccessible to livestock and has become oldfield which we try to keep mowed amid scores of the stumps and still-standing ash trees finished off by the notorious Emerald Ash Borer. See picture of oldfield, recently mowed, below.

Another couple of acres that we have grazed in the past now have such a heavy growth of Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum, an invasive C4 plant) competing with forage grasses that they are hardly worth the work of setting portable fencing The picture below shows stiltgrass on turf that had been grazed into 2016. This piece of ground had been mowed twice in 2018 before the photo was taken on Aug 27.

In 2017, sheep stood at least once on 17 acres of pasture, of which 13-14 acres are decent to good perennial pasture with SOM (soil organic matter) 5.9% to 8.2%. They are mostly gently rolling hillsides with one relatively steep slope of about 15% . Through 2017 we used semi-intensive rotational grazing for the ewe flock until breeding season, when subgroups stay in larger paddocks with one ram for several weeks. In May 2018, before breeding season, we went to more intensive grazing management, aiming for but falling short of “holistic grazing.” This meant making smaller paddocks with, with average shorter on-times than in the past. Deciding when to open a fresh break was based on a field walk, not a pre-set schedule , but most paddocks were sized to be grazed without compromise to plant health in about 24 hours. Maximal holistic grazing can have a fresh break opened more than once a day. We mostly did once a day.

We could not back-fence after every move because there had to be access to shade under trees outside the pasture reached through one of two gates. Predictably, however, the ewe mob stayed mostly on the newest break so that ground behind them was pretty much resting even when not fenced off. We back-fenced through August after four days at the most. Paddocks were bigger on the the third cycle for two reasons: (1) because in a hot dry summer grass comeback was less but was still appreciable after a rainy second half of July; (2) warm season weeds like stiltgrass, hemp dogbane, black swallowart, pinkweed (the list goes on and on) crowded out a good grass or made it hard to browse We have a slide show documenting the first four months of the new program, but to see it you have to have Power Point. Ask Stephen sqs1 (at) columbia.edu.

We also fell short of ideal adaptive paddock management because in May and June the grass grows very fast. Our small ewe mob (40-50) going into a 1/4 acre paddock where the grass was 9-12 inches high could not possibly eat it down to 3-4 inches before they had walked and lain on it so it became less appealing.

When we moved them out there was still so much grass that it had to be bush-hogged; a lot of the edible vegetation was thus wasted . The short-stay long rest program, however, should help with intestinal parasites. The photo shows grass after the ewes had been in the paddock less than a day.

We continued in early 2018 and early 2019 as in previous years to dress the less hilly pasture with what we used to call “compost,” poorly-aerated barn bedding waste that had been stockpiled uncovered for 6-12 months. The average of six samples in 2017-2018 had a C:N ration of about 14 with about 1% N. Graeme spread about about one ton dry weight basis/acre on ~16 acres. This is not high-quality compost. It probably does not promote carbon sequestration when applied to soil and likely generates excess methane while stockpiled. It does make a good vehicle for clover seed. It has been so wet and warm in winter 2022-23 that it’s not been possible to spread manure. That’s the first skip in twenty years.

We don’t employ chemical herbicides. We have, however, used chemical de-wormers ( notably avermectins) regularly as appropriate to age and breeding cycle. Mature ewes are vaccinated against Vibrio. Lambs get lasalocid in their feed to one year of age for control of “coccidiosis.” Other antimicrobials by mouth or injection are given as needed for treatment of symptoms or on schedule as prophylaxis against threats like neonatal pneumonia or chlamydia-caused abortion.

Common milkweed is listed as toxic to sheep but we don’t have much growing in the better pastures and if it’s there spare some patches in mowing. They don’t eat it. We also have hundred of milkweeds around the house and garden that mature as Monarch butterfly habitat. The picture shows a stand of milkweed in late August 2018. In foreground is Big Bluestem Large structure is an icehouse that no longer stores ice. Small one is not what you think; it’s an old incinerator that now stores paint and fuel. The bank is no longer grazed; it’s very inconvenient to get sheep to it.

Our sheep are not interested in eating weeds, not even those such as pinkweed, said to be palatable to cattle, goats and (friends swear this is true) some sheep. They would eat these, I guess, these if there were nothing else they preferred. I’ve seen rams munch pinkweed and even horse nettle. but not with gusto. Photo below shows them browsing pinkweed but they did not take much.

One way to promote carbon sequestration in soil is to get something — preferably forage, but even tolerable weeds– growing on every square foot of soil. Here are two before and afters that show some success in that realm.

slope west of yearling barn Jan 2018 and again in Sept 2018

In Jan the slope above had been frost-seeded with clover, then had 20 seedlings of common vetch planted in July, There’s not a lot more vegetation to show for it, but there’s some. The next pair of pictures, below, has more dramatic results. The left picture is of the east-west fenceline between two pastures in the North park, almost bare and beginning to gully in January. In summer lambs lounge in the shade along this line under the trees. It was dressed lightly with long-stockpiled barn litter carried by wheelbarrow late winter, frost seeded with clover then scatter-seeded in late spring with annual rye sketchily raked in. In Feb 2023, frost seeding was limited to hand-scattering on bare patches because the ground was too soft to run a manure spreader over it in Dec or Jan or Feb.

What progress has there been on the objectives laid out last year?

- Assessing our farm’s current carbon footprint (C-print) using our own tabulations as well as USDA COMET-farm; the English counterpart Farm Carbon Calculator; and the Scottish Coolfarm Tool. I have plugged our data into all three of the established publicly available programs as well as our layout cobbled from various sources. The two programs from Great Britain look at a set of variables quite different from ours in the USA and are hard to apply thought their managers have been very helpful. COMET Farm threw us an un-hittable curve by declaring that mowing pastures even once completely negates any GHG benefits from rotational grazing and spreading stockpiled barn bedding. Stephen at first refused to believe this, but cameby mid- 2019 to think it’s true . Certainly making hay removes carbon from soil though some (not all) of that carbon can be theoretically be recycled by composting manure. Above-ground biomass cut and left lying uneaten will not return its carbon into the soil unless trampled in harder than our sheep do compared to bison or cattle.

- It’s worth noting, though, that if carbon sequestration in trees is counted, our farm’s CO2 footprint would be negative; probably even the CO2-e footprint would be , too. We have at least 6500 trees here. Assuming conservatively that the average one is a 20 year old sugar maple, these are putting into wood about 100 tons of CO2/year . We can’t be complacent about the offset and are working to lower CO2-footprint . It looks looks to be about 65 tons CO2/year, but this figure is in flux, with more guidance needed from COMET Farm in estimating methane and N2O emissions due to enteric fermentation and manure management. A farm’s “carbon footprint” must take these into account, even if that farm does not use synthetic nitrogen fertilizers.

- Lowering the C-print immediately We now buy electricity for the barns and the manager’s house from an ESCO, Green Mountain Energy (100% solar or wind) through Central Hudson. As mentioned above, we had installed solar photovoltaic panels on one barn roof in 2016 , but they don’t have the capacity to supply everything. Jan-July 2018 the panels generated about 1700 kwh. Our new diesel truck gets about 13 mpg where the previous one got 9. Our ewe flock is about 20% smaller than two years ago; so, grain and hay carriage and consumption are less. We replaced the natural gas furnaces and water heaters in two houses with air-sourced heat pump systems in summer-fall 2019 and put a geothermal system into the manager’s house in fall 2022.

- Assessing the health of the soil under our pastures by soil samples and forage testing In 2017 we did twenty soil or forage tests and one CASH (Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health). This taught a lot about sampling methods. In a one-line summary, SOM (Soil Organic Matter) was a pleasing 6-7% in most of our pastures and grass clipped from most was 14-15% protein on a dry matter basis. The SOM was done by loss on ignition. The CASH analysis had a very good score, overall optimal with points off for hardness. In 2019 July we started to use the Microbiometer. This measures mass of microbiota rather than “soil organic matter” or “soil organic carbon. ” I like that principle and the company staff, but had so much within-sample variability that I put it aside to come back to. “Soil your Undies” tests in 2017 and 2018 showed very good destruction of the buried cotton cloth, a testament to soil health. Dr Fitzpatrick at microbiometer said it’s saprophytic fungi more than mycorrhizal ones that chew up the fabric; both are desirable. The 2019 specimen, exhumed after two months, is shown with control.

- SOM is only one measure of soil health. A CASH analysis such as Cornell does comprehends more, but costs much more/sample. Analysis of microbial life as with Microbiometer gives a different perspective. Eyeball observations of earthworms and macroarthopods adds a lot. Forage analysis helps. Plant and animal and insect biodiversity give insight. Estimating above ground biomass helps. There’s really no one dimension to hang your hat on. Based on our soil density estimates we reckon that the top 30 cm of each acre of our good pasture holds about 27 metric tons of carbon. Following the objectives of the 4p1000 initiative we’d like to add about 0.11 ton/acre/year. Evaluating progress will be very hard.

- Assessing the pros and cons of how we compost barn bedding waste and spread what results Good help here from Mary Schwarz at Cornell and the Agro-1 manure lab. Overall, our method (stockpiling barn floor waste uncovered in a wide rectangular pile for 6-9 months without turning) is not optimal, but yields what looks by the numbers useful top-dressing. In 2019 we went to narrower windrows for stockpiling but cut way back on sampling, which is expensive. Besides, the stockpiles are very un-homogeneous. There’s an awful lot to learn on how to use livestock barn floor waste. The secret won’t be in the C:N ratio or the tonnage of organic matter thrown on per acre. The work of Prof David C. Johnson at New Mexico State makes it clear that it’s the ratio of fungi to bacteria in compost that promotes carbon sequestration by mobilizing mycorrhizal fungi around roots. Our anaerobic composting technique will not maximize these good microbes. We’ll keep spreading the stockpiled material to add N to the soil. We also have quite a lot of clover in the two best pastures, which helps with N. Here’s the stockpile November 2017.

- Assessing consequences of manure and urine dropped on the ground I had planned to forget about this, thinking it may be important for cattle on pasture that poop out much more and and trample more than do sheep. In Jan 2020 a twitter post from an Irish sheep farm alerted me to the importance of dung beetles in pasture health. We have no dung beetles, likely because we’ve been using ivermectin and moxidectin for s few years. Learning more about what they do by themselves and as a keystone genus in soil life made me decide we must stop using avermectins except maybe once a year in midwinter and populate our pastures with several species of dung beetles. They can be bought by mail from Marvel Farms in FL and I’ve found a FB page where people offer advice, even to collect some for those in need. The beetles wrangle manure balls underground where they do more good for the soil than air-drying atop. Greatly reducing or quitting avermectins will give us a jolt though I don’t think we have Haemonchus (barber pole worm) here. Many writers say that proper intensive rotational grazing such as we aspire to will reduce worm burden because any worms dumped out are left hostless for so long they die. In 2020 I gave up on trying to foster dung beetles.

- Assessing carbon storage in trees, which cover more than half our total acreage With the essential help of foresters from The Black Rock Forest Consortium in Cornwall NY we made a start in 2018. The team tallied what species (both native and non-native) are here now, which ones predominate in various mini-locales (limestone ridge, bottomland, waterside) and provided figures to estimate the current carbon storage and the annual rate of carbon sequestration.in the definitely-not-old-growth woods here. As of July 2023 we have more than 80 species identified on the place, counting species that we have planted. Norway and sugar maples are the most common species of big tree. Black jetbead (Rhodotypos scandens) is the most common bush that’s more than a foot high. It’s an exotic invasive that we started noticing about ten years ago. I used to pull out a lot of it, thinking it was crowding out more desirable species. Bad idea. It can help to prevent erosion. Moreover, growth of desirable native species is severely limited anyway by deer. The BRF folks had me build two small deer exclosures to encourage growth of eastern white pine from seed and protect some black walnut whips bought from a nursery. They also advised girdling some Norway maples and ailanthuses to eventually get more light to the understory. That’s still not been done as of Feb 2023. The deer exclosures were knocked down by falling limbs and not repaired. The local deer population is way down in the last two years because of the endemic hemorrhagic disease; I’d say from casual spotting it’s down more than 50%.

- We have also begun efforts to get more deliberate diversity of desirable species into what grows in our pastures. An inventory of what’s there in 2018 is off to a slow start because Stephen finds it so hard to identify grasses despite books, you-tube lectures etc. So we can’t tell you yet what wanted grasses predominate and where but promise to work on it. Identifying weeds in pastures is much easier than differentiating grasses. “I have a little list,” which will become a blog post someday. Weeds, I have learned, can themselves be good for the soil even if sheep don’t eat them, as long as they are mowed before gaining ground, which is easier said than done. We frost seeded very successfully with two kinds of white clover late last winter, not visibly successfully with chicory. We did some small test seedings in May of Ray’s crazy mix, a cocktail from King’s, along with annual rye. Tried also some plantings of big bluestem and common vetch in trouble spots; can’t say yet if either took well. the big blues are still alive, need a couple of years to take off. The vetch bombed. In Jan 2020 Graeme sprinkled 25 lb of Alice white clover seed divided over 50 loads of stockpiled barn waste he spread over the main pastures. This has worked well as a frost -seeding method.

- In May 2020 we got a small no-till drill but the ground was too wet to use it then. For a lark in September 2020 we planted Ray’s Crazy Mix from King’s AgriSeeds into a recently grazed pasture. The picture shows plants drilled in September into north park. You can see the drill rows. In late September 2019 Graeme had drilled inoculated burnet seed from Green Cover Seed with into the north arm of the main park; that didn’t succeed. We will be trying to put more annuals into the grass, including forbs and brassicas. I’m sorry to say we decided to sell the drill in 2023, almost in showroom condition. We found that for putting annuals into our pastures the ground was always too cold and wet in April and early May, then had too much grass to drill through, then was too dry in late summer. It was a good try. We donated the drill to Glynwood in the end.

- In the last two years, I have concluded that encouraging mycorrhizal fungi is one of the best things we can do for soil health. This has been known for some time though not to me. Eager to try out fungi-rich soil inoculants in combination with grazing ruminants, we did a test plot in summer 2020. Three times, about a month apart, Graeme sprayed “Liquid Humus” from Penn Valley Farms in PA onto an acre of sward that’s been grazed once a year for about two days and mowed several times a summer. The SOM pre test was 3.2% (low for our farm), pH 5.5. This area has never been part of the regular three cycles per summer rotation. The forage quality was poor, with a lot of stilt grass. In September we put the ewes in briefly. For a better test, grazing ewes would have followed each application after a few days. Here’s Graeme with the boom sprayer in June.

- We made fungi-rich soil inoculant in our Johnson-Su bioreactor and in 2020 used the a liquid cold-brewed from it as a foliar spray on the patch of poor-quality pasture where we’d used the Penn Valley liquid humus. This should will be better for soil microbiota than our customary low-rate (1-2 tons dry matter/acre) application of long-stockpiled barn litter. We may use the latter more intensively on smaller areas along with the soil fungi-rich inoculant. Our home built J-S reactor was started March 28 2019, and we joined the registry at Chico State. The material from our bioreactor was called by Dr Slaughter at Earthfort “some of the best Johnson-Su I’ve ever seen.” We used it as a seed coating in 2021 following Dr Johnson’s recipe, but it was laborious to make a fresh batch daily and we only did a couple of days, on the old victory garden flat spot shown above.

- Biodiversity of flora and fauna is another thing to work on . In the last year we as not very keen observers have sighted (list from memory, not a log) beaver, weasel, woodchuck, white-tailed deer (lots), red fox, coyote, gray squirrel, chipmunk, rabbit, skunk, opossum. Not sighted, but raided Brian Wilson’s beehives near our front gate, black bear. Snapping turtle , frog, salamander efts. With wings: wild turkey, Canada goose, bald eagle, red-tailed hawk, Eastern bluebird, great blue heron, little green heron, American egret, pileated woodpecker, downy woodpecker, hairy woodpecker, Carolina chickadee, black-capped chickadee, ground dove, nuthatch, cardinal, flicker, bluejay, cowbird (grr!), grackle, English sparrow (grr,), house finch, robin, goldfinch, crow, tree swallow, American oriole, ruby-throated hummingbird, slate-colored junco, various seagulls et al, mallard, wood duck, turkey vulture, wood thrush, osprey, catbird. There’s a lot more looking to do. Flying mammals: bats and once, in our house, a flying squirrel. Amongst insects favorites include earthworms, honeybees, ladybeetles, dragonflies, damselflies, butterflies and some outdoor moths like Cecropia. Spiders and bumblebees have their place. Un-favorites abound, including greenheads, deerflies, mosquitoes, chiggers, stable flies, closet moths, tent caterpillar moths, chiggers, yellow jackets, wasps, brown marmorated stinkbug, I could go on and on and will later. On my bucket list is to inventory plant life beside the trees and to plant more species of trees. Here is blue-eyed grass under an electric fenceline.

- In early May 2019 we planted 4 pawpaw and 4 persimmon on the turf east of Graeme’s house 4 red maples in main and north parks and 4 black locusts in fencelines. These are all tiny slips enclosed in wire cylinders for protection from foragers and mowers. Black walnuts planted last year are mostly doing well, now about 2-3 feet high and very leafy. In early May 2020 five shad blow near the house and 5 sycamores near the stream. The shad blows are all still going in 2023, as are two of the sycamores. In 2022 we also planted 150 living stakes of various trees, mostly along the Sawyer Kill, hoping for streambank protection. Only a couple made it to autumn, two elderberry and two button bush. One of the former and both of the latter are alive in 2023. The season was just too dry. Four more sycamore slips were planted along the Sawyer Kill near house bridge fall 2022; three made it into 2023. We have joined American Chestnut Foundation and have three hybrid seedlings in pots, carefully tended. In summer 22 I stuck four willow branches (Salix babylonica, not native) in a wet spot of the main park near the house bridge. They came from a big limb lost in the Feb 2022 ice storm . As of summer 2023, two are flourishing.

- The streambank buffer along the Sawyer Kill was by spring 2023 a jungle of invasives. This motivated us to reduce their volume sharply, to start planting native species in the now-opened spots and to encourage native trees, flowers and vines discovered in the clearing-out effort. These included, happy to say, Honey locust, American hop hornbeam, hickory, american bladdernut, slippery elm, spicebush and buttonbush. The project is going on as this is written in late July.

- i Naturalist, a social media platform for naturalists amateur and professional, has been a godsend. Strongly recommended

In 2018 Stephen wrote a series of blogs about carbon and agriculture that are on the web site under News and Views. Added-to in 2019 with blogs about methane.