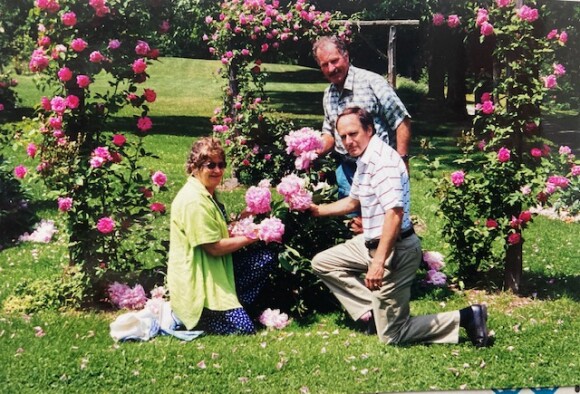

Trish and Gordon Levet with Stephen, Anchorage Farm 1999 photo E. Shafer

Writing and video by or about Gordon Levet

Breeding Sheep that have a high immunity to worm challenges

Gordon Levet, Wellsford NZ

November 2024

First an overview of worm challenges and the role of the immune system. In feral sheep and in all mammals, worms have always been present. In sheep there are six main worm species. All cause ill health and stifle growth with some deaths occurring. By far the deadliest is Haemonchus Contortus, commonly known as the Barbers Pole worm – BP worm – because of a red spiral in its entire length – blood. It is the only one that sucks blood, with each worm sucking a mil of blood a day. So, 500 worms would remove half a litre of blood every day. Females produce 10,000 eggs each day. It is truly a killer worm. The natural habitat of feral sheep are the arid hills and mountains around the Mediterranean, Asia Minor and the Rockies of North America. In small mobs, they would browse on brambles like wild roses and numerous small plants and shrubs. They would only ingest worm larvae when grazing on grass around streams and other moist areas. Their immune system evolved to control the low worm challenge animals face. Worms play an important role in nature because they are one of the first to stimulate the immune system into action.

Now fast forward to our present farming methods. We have changed the diet of sheep from browsing in small mobs over huge areas. Now we farm sheep in big numbers on small areas of lush pasture where scientists estimate that one kilogram of herbage would contain 10,000 worm larvae. For hundreds of thousands of years, the immune systems of sheep have been ‘programmed’ to control very low worm challenges. So, our modern sheep now have a far greater worm challenge to face, probably a hundred-fold increase or maybe a thousand-fold, no-one knows. So, we need to breed sheep that have a quicker responding and stronger immune responses to control the greatly increased worm levels.

Farming in a warm, wet, humid environment in NZ that favours all parasites fungi that produce toxins that kill sheep and cattle i.e. facial eczema, diseases like pneumonia that causes 94% to 96% of lambs in autumn to have lung damage that results in deaths every year, always 2% to 5% and in some years, higher. I have also had a major worm problem where the deadly BP worm is the dominant species. However, on the positive side, these are the ideal conditions to breed sheep that have resistance to all these health problems.

In the 1980’s I became aware that some lambs were more affected by worms than others, so believed that genetic factors could be involved. I had already succeeded in breeding sheep to be resistant to footrot and scald in the previous 30 years, by the simple method of ‘culling the worst and breeding from the best’. So believed the same selective breeding may succeed when applied to the worm problem. In 1986 I discussed this subject with a parasitologist, Dr Tom Watson who agreed that it would be possible to breed sheep that were resistant worm challenges. He provided protocols to be followed to begin this long-term mission, which some thought would take at least 25 years. These protocols were to drench all ram lambs, then about 8 weeks later, take a dung sample from each lamb, send them to a laboratory for worm egg counting – faecal egg counting or FEC for short. All lambs were then drenched. The whole process was repeated a second time to achieve greater accuracy. These egg counts indicate roughly the number of adult worms present. When the egg counts become available, the average count for each sires’ ram lambs is assessed. Over the years, I have used 10 to 12 sires. In the early years, the average worm count varied greatly with a five-fold difference between the best and worst sire. This variation was an early indication that progress was possible. It was then a simple matter of using the best son of the best sire to mate with the second-best sires’ daughters. Conversely, the daughters of the best sire would be mated with the best son of the second-best sire.

Four years after I started a very long journey, our NZ Department of Agriculture set up a national programme for ram breeders to join to breed for worm resistance with the same protocols I was following. It was called Worm FEC. About 30 joined with different breeds. But many left within 5 years when it was realized that it was all hard work, costs and no tangible financial rewards. Over the years, the membership wavered between 25 and 30. In recent years there has been renewed interest in the genetic solution as drench resistance has become an increasing problem.

In NZ we have had a national breed programme since 1967 which with the aid of computers ranks all animals in a flock for many traits. This programme is called Sheep Improvement Limited or SIL.

Worm resistance is scored by DPF (Dual purpose Fecal Egg Count) which I do not fully understand. I believe the figure is a combination of the sheep’s individual faecal egg count – FEC, the sire’s FEC, together with the dam’s sire and the siblings FEC. In other words, the historical background of FEC. The figures generated are a minus figure for those that are more susceptible to worms and positive figure for resistant animals. Thus, a sheep with -300 would be moderately susceptible to worms whereas sheep with a positive figure of 300 would be moderately resistant. Those that have a figure over 700 would rank in my opinion as highly resistant to all worm challenges. SIL also ranks all animals for all traits which is within the flock ranking. There is also a national ranking of rams for those that are breeding for worm resistance. It took me 26 years for my flock to reach an average of 296. This figure was compromised because of using an outside sire which had less resistance. The rate of progress increased rapidly to reach a DPF of 749 nine years later in 2020 when no outside sires were used.

In breeding for resistance, I did the opposite to best practice to minimize a worm challenge. My aim was to give lambs the highest worm challenge possible. Then the first FEC would reveal lambs that were resistant to this high challenge. I would also indicate those that reacted the earliest. For example, the 2019 born ram lambs – 399 – that had never been drenched had an average FEC of 3733 in the first FEC. The highest 25550, the lowest 105. There were only 13 under 500, 6 were by a sire who had only 28 sons tested. The second test 4 weeks later average was only 122 with 70 nil counts. This led me to claim success in my long mission.

What does all this mean for breeders who wish to breed for the resistance trait?

There is now semen available to ‘short circuit’ the long process of starting from scratch as I did. Let me explain. Using the semen from a ram with a DPF of 700 over an average non-resistant ewe should result in progeny varying from nil to 700, averaging 350, a figure that took me more than 26 years to reach. I would rank the progeny of this ram as having moderate resistance which would require less drenching. Using another ram having the same DPF of 700 and the progeny should have an average DPF of over 500. Now use a ram with a DPF of 1000 over the daughters of the second ram and the average should be around 750 which took me 34 years of long hours, much costs to achieve.

However, this is all hypothetical. The only certainty with genetics is uncertainty.

**************************************************************************************************************