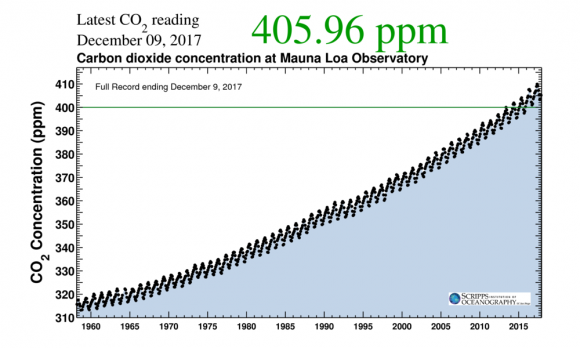

The Keeling Curve: Atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa Observatory, annual peak and trough by year 1960 to now Source Scripps Institute

The Keeling Curve: Atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa Observatory, annual peak and trough by year 1960 to now Source Scripps Institute

This is the fourth of a series of essays about American agriculture and climate change. The first three, in order of appearance are these:

2. comparing-carbon-footprints-of-world-and-american-agriculture

3. Fossil fuels in the carbon footprint of American agriculture

Abstract: American farmers and ranchers generally oppose a “carbon tax/fee,” even a revenue neutral proposal like carbon fee and dividend (CFD). CFD today does not grasp the situation of agriculturalists. Most of us would like very much to reduce the carbon footprints of our own operations, to help lessen “weather volatility” by using our farm and ranch lands to pull CO2 from air into long-term storage in soil and by these actions to make our farming future more secure. A carbon tax is meant to impel these desirable –indeed necessary–steps. Yet, going into them costs money up front that most of us can’t afford without taking more debt. Committing a portion of the revenues expected from a carbon fee to direct monetary support of “carbon farming” would get ranchers and farmers to support the crucial objectives of CFD in droves.

American Farmers and ranchers almost all oppose a “carbon tax” like that proposed by Citizens’ Climate Lobby even though under carbon fee and dividend (CFD) one hand gives back to most households more than the other took . [How CFD works is explained in Appendix 1 after the click here to read more break below. ] This essay gives the views of a health scientist and farmer on why American agriculturalists don’t want a carbon tax, even one as truly populist as CFD, and on what could be a remedy.

The financial security of the typical American farmer or rancher (used interchangeably) is threatened. [For background see Appendix 2 ] The average farmer owes money to the bank and/or to dealer(s). He has to buy every year seed, fertilizer, pesticides, fuel etc if he wants to bring in a crop. The average American farm is losing money, though the household that owns and operates it may be doing all right with off-the-farm jobs Few Americans farm to make a big profit; we have other motivations such as love of land and animals, of producing good food. In this situation, an additional tax looks a terrible imposition.

Regardless of how the net revenue from the “fee” or “tax” would be distributed, farmers and ranchers would be hurt more than any other occupational sector so vital to national well-being. Three reasons: ranchers and farmers are usually (1) self-employed as regards the farm (2) have a mechanized operation that relies heavily on fossil fuels (3) have little control over the prices our produce brings.

Whether a subway conductor comes out ahead or behind on the carbon fee dividend depends on how much her household laid out in carbon fees, not how much her employer did. By contrast, nearly all farmers are self-employed, even if they also work off the farm. Profit from the farm is profit to the family; loss on the farm is loss to the family. Thus when carbon surcharges paid by his farm business exceed the household dividend, the farmer is penalized as if his household is careless with carbon. It might be average or better than average for its income stratum if farm business is not counted.

The outcome of a carbon tax/fee that looms largest to most Americans would be price increases at filling stations. Ranchers and farmers are in the same boat. In the USA nearly all rely heavily on fossil-fueled machinery that is expensive, long-lived, hard to substitute for and hard to share, since everyone tends to need it at the same time.

A householder can relatively easily replace a six-year old gas guzzler with a fuel-sipper. For a farmer, however, the capital cost of replacing certain pieces of equipment can be much greater, digging into an already thin (or negative) profit margin. In many vehicular enterprises it is routine to pass a fuel surcharge to customers, who grumble but endure. The food grower, however, is rarely secure that her new production costs will be assumed by the middleman then relayed to the retail customer. Even if the middleman does pick up the producer’s extra costs, to pass to end-users, there’s still the risk that rising prices in the store aisle will decrease future demand, and with it, future gross income to the farm.

American farmers feel punished by carbon-tax proposals, as if held directly and solely responsible for the big carbon footprint of a food production system that has gone geophysically and nutritionally off course in the last two hundred years.

Advocates of a carbon fee and dividend certainly do not expect production agriculturalists to absorb 100% of the carbon fee that came to them, nor to pass on 100%; rather, to find a middle ground. They picture that farming and ranching would react to a carbon fee by (among other things) by using less fossil fuel over time. There are two divergent ways to “less:”

- Reduce through management changes the “carbon foodprint” of each foodstuff without affecting its quality or place in the national mix. The foodprint of all foods summed goes down without compromising quantity and quality for the population.

- Maintain the current carbon foodprint of each foodstuff but selectively thin the most carbon-intensive components. The summated foodprint declines, with a falloff in quantity and quality that is unthinkable in the eyes of some (e.g. meat-eaters) and highly desirable in others’ (e,g, vegans)..

A compromise between the two paths is preferable to either extreme.

Adjusting to the shocks of a rising carbon tax would require rapid changing of practices in cropland and livestock management and a re-alignment of consumer priorities. These changes are required for global health. Also required is fiscal help early on to compensate ranchers and farmers for the costs of transition to those new practices.

Thoughtful advocates of CFD hold that moving to practices like “regenerative farming” to lower the carbon footprint of U.S. agriculture will recompense all the costs of transition in a few years while improving the soil and the atmosphere. I can’t agree. The proposed dividend to households cushions the hit of a carbon tax/fee on most households making a good-faith effort to lower their carbon footprints year by year. This is no such cushion to households in a farm business that cannot quickly at no cost reduce direct or indirect greenhouse gas emissions.

In my opinion there needs to be an adjustment to whatever carbon tax arrangement is proposed in Congress that will build in help to agriculture. A slowly-sunsetting flow of some of the net fee revenues would be practical. Besides that, there should be federal and state policy to monetarily reward movement toward farming that is much less GHG-intensive than today’s mode. This could be tax credits for carbon sequestration practices.

Carbon tax advocates must push for such policy at the state and the federal level. We must not pretend, though, that even a generous and easily- administered tax credit for carbon sequestration in soil will spare all farmers and ranchers from short-term fiscal harm. It won’t. The grim reality is that without help some will get plowed under . The help to prevent that misery could come from revenues of CFD.

A map to carbon footprint reduction in food production unfolds in the fifth essay of this series, “Carbon Foodprint.”

Appendices below this break

The Keeling Curve as a banner to this essay highlights the trajectory of rising CO2. This is an emergency.

Appendix 1 In CFD, all the net revenue from the “carbon fees” is distributed directly to all U.S. households by household size (maximum of three shares each) without regard to means or location. The 2016 Household Impact Study from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis concluded that households in the lower seven deciles of income would on average get back more per month from the dividend than they had laid out in surcharges on “carbon,” which here means fossil fuels. Even in the highest two deciles, 57 % of households would see a net benefit or a small loss (less than 0.2% of income). Why, then, wouldn’t farm households, hardly over-represented in the top two deciles of income, show interest in CFD ?

Appendix 2.

First, some background on American farms, mostly from the last Census of Agriculture, which compared 2012 to 2007. No distinction is made between “farm” and “ranch.” A farm generated, or expected to generate, > $1000 of agricultural products in a given year. In the year 2012,

- The United States had 2.1 million farms – down 4.3 percent from the last agricultural Census in 2007. This continues a long-term trend of fewer farms.

- The amount of land in farms in the United States had declined from 922 million acres in 2007 to to 915 million acres. This decline of less than one percent was the third smallest decline between Censuses since 1950.

- The average farm size was 434 acres. This was a 3.8 percent increase over 2007, when the average farm was 418 acres. Middle-sized farms declined in number between 2007 and 2012. The number of large (1,000 plus acres) and very small (1 to 9 acres) farms did not change significantly in that time. 55% of farms in 2012 were less than 100 acres. Graph 1 (made by me) shows distribution of farm sizes by acreage. In 2002 the median (distinct from “average” or mean) was 80 acres.

Graph 4.1. Distribution of farm sizes in acres, USA 2012 among total of 2,109,000 farms. Data re-compiled from Full Report Census of Agriculture 2012.

- The average age of principal farm operators was 58.3 years, up 1.2 years since 2007, and continuing a 30-year trend of steady increase.

- U.S. farms sold nearly $395 billion in agricultural products in 2012. This was 33 percent – $97.4 billion– more than agricultural sales in 2007.

- In 2012 75.5% of American farms had a gross sales income under $50,000/yr. For 57%, gross sales were less than $10,000/yr. Only 46% had net positive cash flow.

In 2017, the 8% of American farms with gross sales value more than $500,000/year had 83% of the net cash income, while the 80.6% of farms with gross annual sales value < $100,000/yr averaged a slightly negative net cash income, as they had in seven of the previous eight years.

In 2017 US farm expenses totaled $310 billion; interest payments ($18.7 billion) exceeded outlays for pesticides ($15.2 billion), which outstripped those for fuel and oil ($13.8 billion). Note that “Fertilizer and lime” accounted for $21.8 billion of farm expenses.

Two excellent articles from a few years ago by Tom Philpott about the financial stress of being a farmer or rancher. Read this one first

https://www.motherjones.com/

https://www.motherjones.com/